⚰ HTTP://CURTISROTH.NET ⚰

[UPDATED: 07_17_2023]

Maybe the real architecture was all the friends we made along the way ʕ-ᴥ-ʔ

Hello, I'm an Associate Professor at the Knowlton School. My work mostly consists of images, objects, and texts that examine how technology and work change us.

My CV can be found here.

My Instagram can be found here.

⊿ AT THE MOMENT ⊿

I'm writing a book about workstations.

⊷ CONTACT ⊷

E-mail:

curtis.allen.roth@gmail.com

Mail:

275 West Woodruff Avenue

Columbus, Ohio 43210

|

❅ GOING FRAGILE ❅

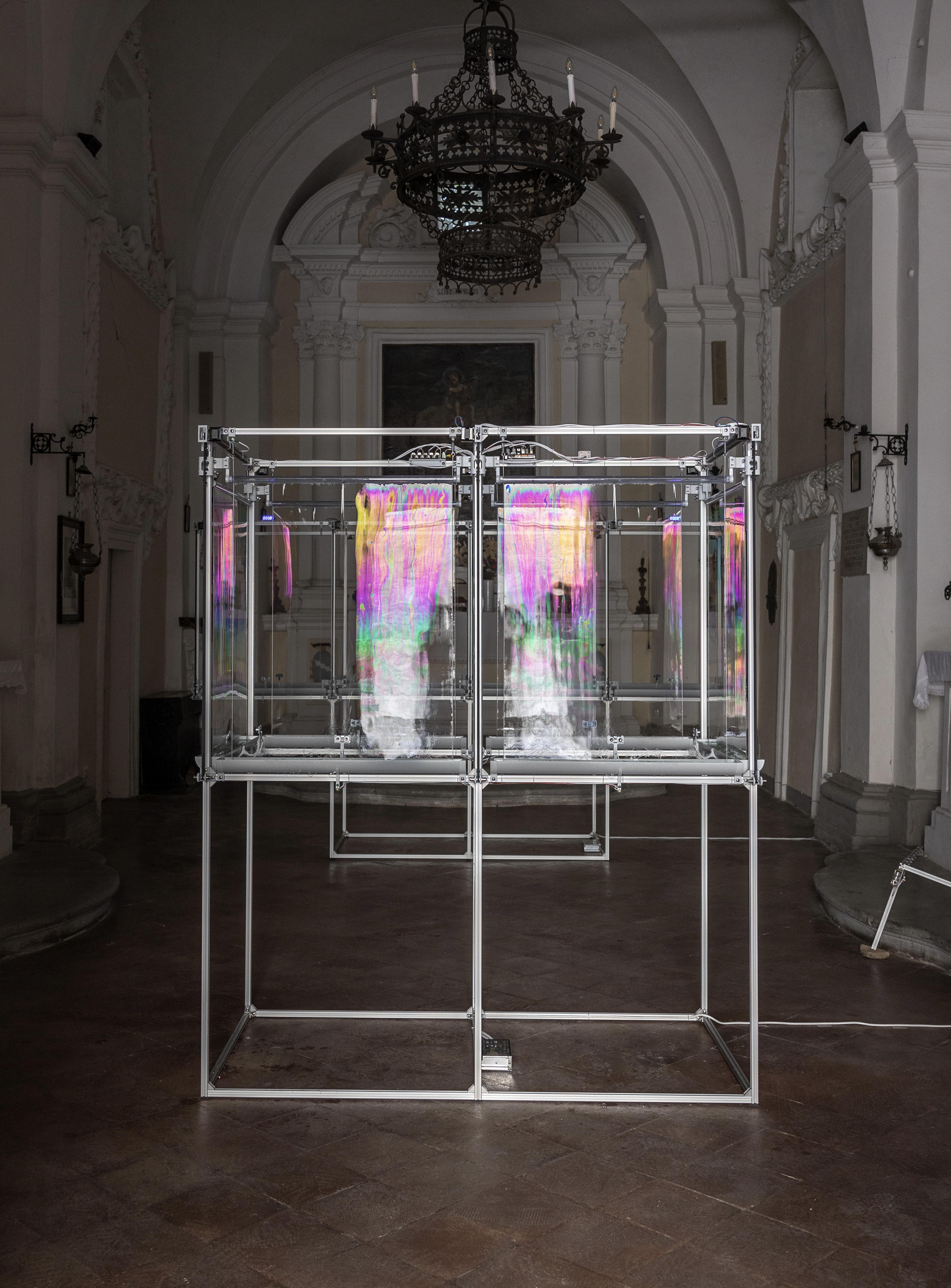

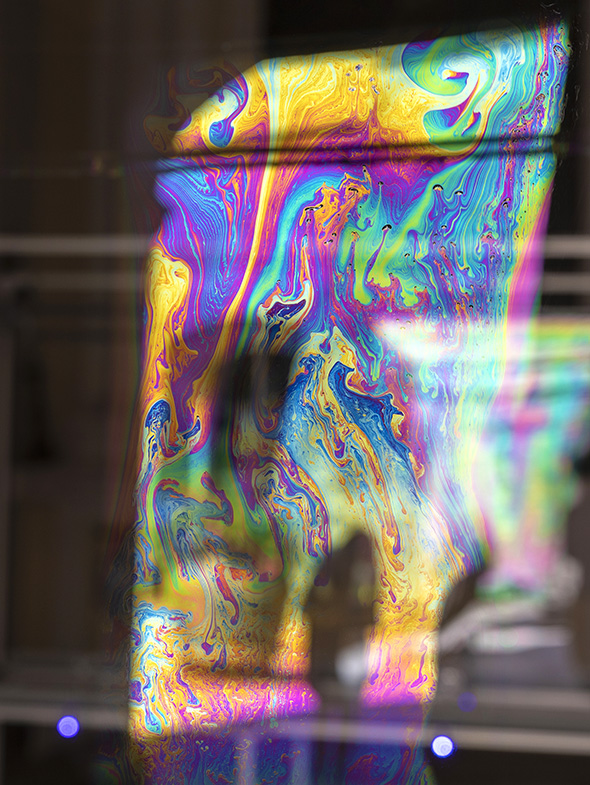

[INSTALLATION] 2022_WOJR/Civatella Ranieri Architecture Prize

![]()

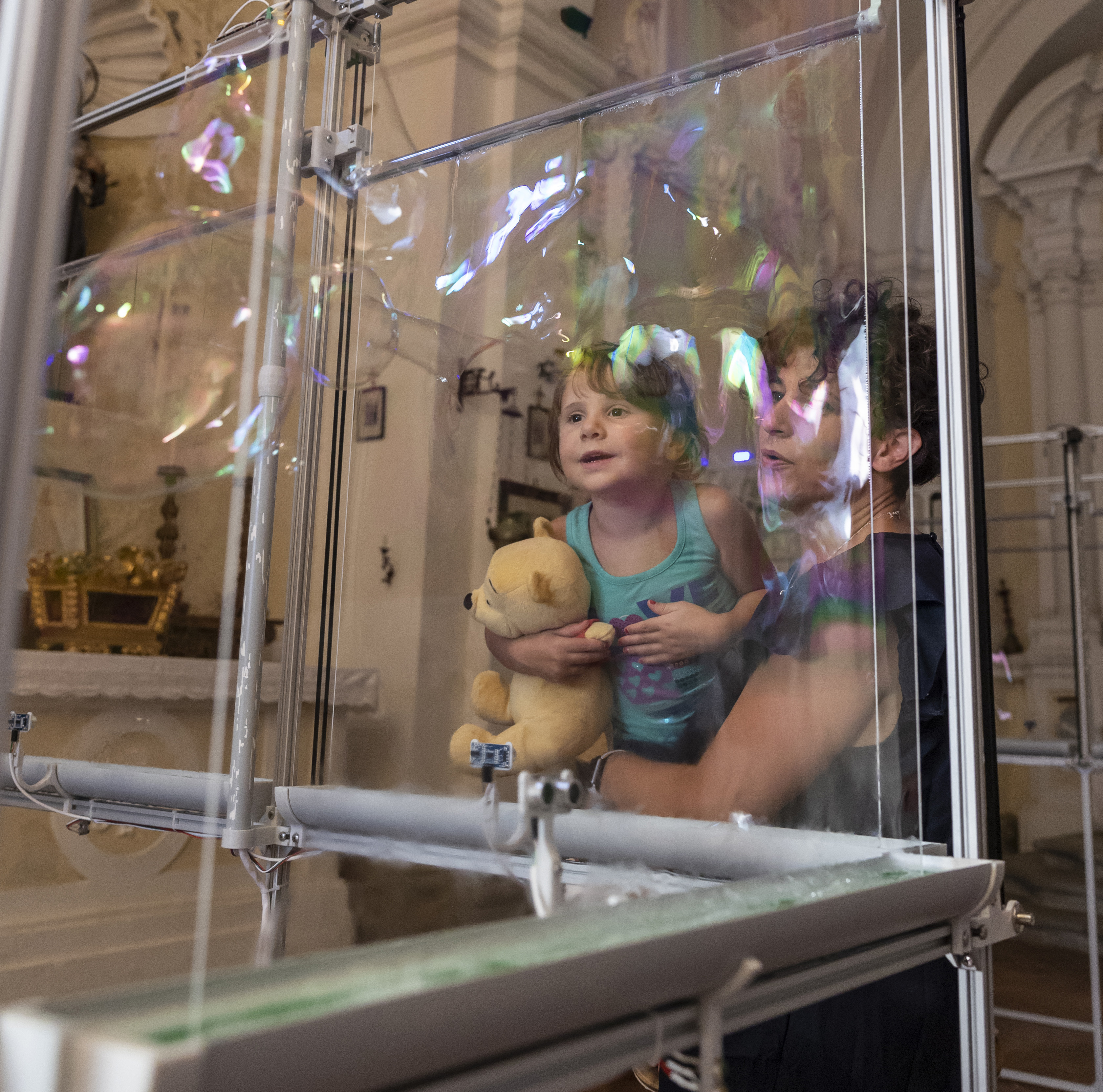

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfroni

Going Fragile is a temporary weather station consisting of four room-sized computers in a 15th century castle, inflating thousands of delicate soap bubbles over the course of an evening. Each bubble, connected to an online database, will act as a sensor for recording the complex interactions between indoor air, the castle’s human and non-human inhabitants, and the leaky perimeter of the stone structure itself. The work reimagines the architecture of Civitella, not as an defensive edifice, but instead as the fragile formation of atmospheres made and maintained by all those who inhabit it.

Many thanks to WOJR and Civitella Ranieri Foundation for the chance to produce this project. As well as the staff of Civitella Ranieri for their support, in particular: Diego Mencaroni, Greta Caseti, Ilaria Locchi, and Sandra Popadic.

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfronis

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfronis

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfronis

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfronis

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfronis

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023

![]()

Civitella Ranieri, 2023, Photograph by: Giulia Manfronis

|

⚭ TOGETHER FOREVER ⚭

[TEXT] 2022_Published at LOG

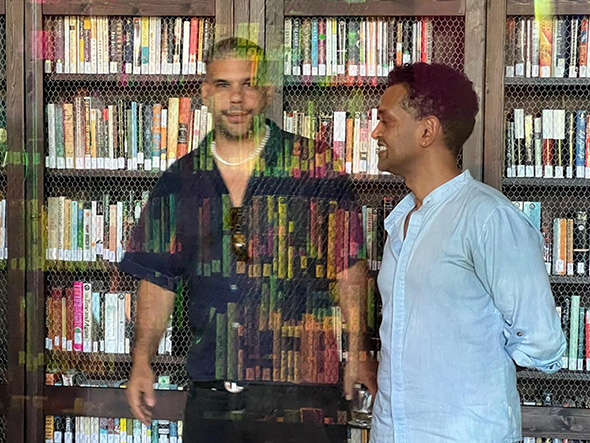

![]()

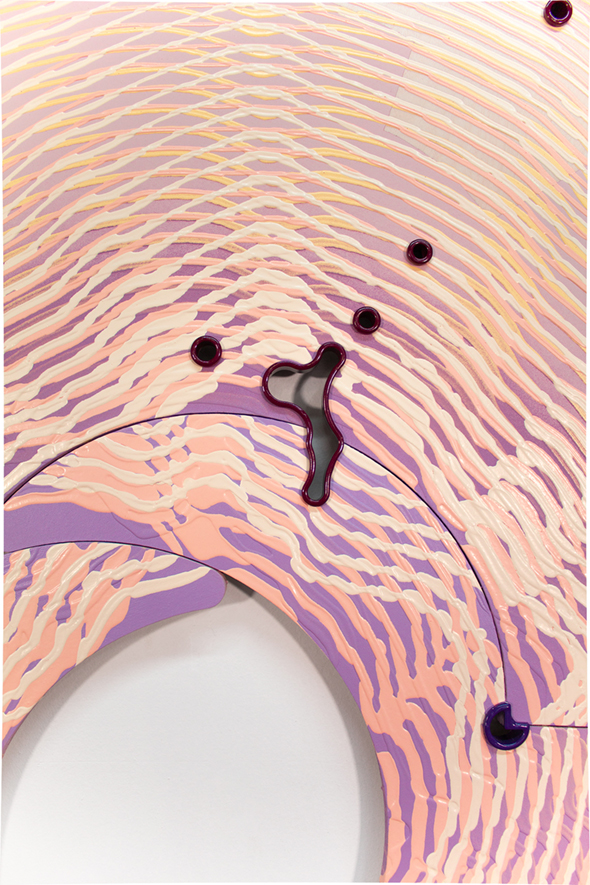

Groupware Painting Detail, 2021

A funny thing about chance is that it makes the future feel a little more tangible. I learned this with a JavaScript application called RandomMap.js. I wrote it out of anxiety in the spring of 2020, a couple days into that limbo when we all imagined quarantine lasting two weeks. The app was reassuringly user-friendly – I would position a handful of points on my screen, hit a button in the lower left labeled “simulate,” and then just wait. Thirty-odd minutes later, my CPU fan would shut off and 100 unique lines would populate a folder on my desktop. Each squiggling line connecting the points I’d positioned previously, from A, through B, to C. Most of the lines were pretty dull, but every epoch would return a few that struck me in ways that were difficult to describe. I liked them. So I’d save them, delete the rest, and simulate a hundred more. Something about the way each simulation escaped my expectations felt comforting at the time. Once or twice an hour, anticipating a future in the form of 100 wobbling lines that were always a little worse than what I’d hoped for but better than I’d feared

RandomMap.js was preceded by its namesake, Roy Ascott’s N–Tropic Random Map I and II, a pair of wall-mounted sculptural pieces made by the cybernetic artist in 1968. They also used chance to pull the future into the present. The two pieces appeared at the tail end of a series of scripted games that had preoccupied Ascott since 1965. Each began with a game board – a sheet of wood larger than the artist’s arm span, laid horizontally in the center of his bare studio. Using a variety of distancing techniques, from blindfolds to randomly dropped rulers, Ascott would encircle the board, layering a network of marks across its surface. At each intersection of the network, he would toss a coin to determine which line would trim the others. The resulting figures were cut from the board with a jigsaw. Each round of the game subtracted additional figures from the panel until the next cut threatened to cleave the board entirely. What was left was a blank silhouette, outlining evocative figures that recorded Ascott’s encoding of his body while inviting the pareidolia of a viewer.

One peculiar thing about his experiments with chance is that since then nobody has known what to call them. They’re something like tabletop games, performed through protocomputational code, resulting in objects that are heavy like sculptures but hung like paintings. Ascott just called them plans. Less architectural plans than low-tech analogs for planning a digital network to come. For Ascott, these experiments in procedural authorship made a future technopolitics more tangible. He called this future the Cybernetic Art Matrix (CAM), a soon-to-be global web of creative production in which “anarchic” crowds would interact with hardware, communications infrastructure, and artificial intelligence to produce vast informatic artworks at the scale of planet Earth itself. The rest of us would just call it the internet.

But before the net was envisioned with a coin toss and a jigsaw, it was a board game played by cold warriors. In 1953–1955, Ascott worked in radar operations for the Royal Air Force, stationed in the graduated rows of a Fighter Control bunker overlooking a large horizontal map of the North Sea. During those formative years, the artist and his fellow duty officers were fed real-time aircraft positions by telephone from remote radar stations. The officers would relay those positions to human “plotters” who moved physical analogs of fighter planes like chess pieces representing faraway friends and enemies across a continental playing field. The peculiar board game was Ascott’s earliest encounter with a cybernetic network, one in which computation pulled the future into the present by predicting the impending maneuvers of remote fighter planes. As biographer Kate Sloan observed, “Ascott, like so many of his contemporaries, had experienced the most sophisticated technologies of the age in the context of the military, providing in a very real sense, a window on the technological future.” But while Ascott’s contemporaries would anticipate the World Wide Web through romantic analogs like superhighways or electronic frontiers, his particular internet emerged out of technologies designed to track and predict the movement of bodies through space, first jet fighters in the North Sea and later the erratic movements of his own arms. Ascott’s intricately scripted field games separated his gesturing hands from his eyes and from his thumb flipping a coin – entangling his body with a battlefield of intersecting “beams . . . of pure information.” It was an internet made of loose limbs, and it seems to me that’s the most accurate analog of the internet we eventually got.

Software Extensions

For a few months prior to building RandomMap.js, I’d been collecting the gestures of a hundred strangers I’d met on Amazon Mechanical Turk, a platform designed to coordinate a quarter of a million remote crowd workers to perform discrete “Human Intelligence Tasks.” These are scripted jobs, designed to mine the embodied faculties of remote workers like their visual cognition or physical coordination – faculties that would be difficult or impossible to automate otherwise. Microlabor platforms like Mechanical Turk are only the most obvious loose limbs of our contemporary internet – human beings, employed through gigs, extending vast computational networks with their own bodies. Artist Sebastian Schmieg describes them as human software extensions, “bodies and minds that can be easily plugged in, rewired and discarded.” Today, these human software extensions moderate our flows of content, optimize our user experiences, or buy our groceries during a viral pandemic. Some see it all as a new kind of feudalism. In any case, we’re good at forgetting that the smooth flows of our superhighways are greased with the exploitation of unseen bodies at the other end of the terminal.

In exchange for a few dollars, I asked each Mechanical Turk worker to repeat scripted on-screen movements with their pointers, leaving me with a database of gestural information like the predicted arc diameter of an anonymous worker’s arm, the direction their mouse is most likely to move from a static position, or the average acceleration and deceleration of their wrist as it encountered new content – each entry linked to a hundred individual PayPal accounts. For every RandomMap.js simulation I’d later run, a handful of workers’ gestures would be sampled to jiggle each of the 100 wobbling lines. A hundred lines drawn by aggregating the probable movements of remote bodies stored in a database on my desktop, with financial royalties proportional to each worker’s contribution distributed after every simulation was returned. I figured that with the right algorithm you could predict gestures like jet fighters in the North Atlantic. Turns out someone else thought of that first.

In 2011, the US military research and development agency DARPA launched the Active Authentication program. Their goal was to develop novel ways to validate the identity of console users based on measurable biometrics. In DARPA’s words, “Just as when you touch something [with] your finger you leave behind a fingerprint, when you interact with technology you do so in a pattern based on how your mind processes information, leaving behind a ‘cognitive fingerprint.’” After surveilling the physical gestures of 99 subjects for 10 weeks, one group of DARPA researchers in Sweden was able to detect imposters after 18 seconds of keyboard activity and 2.4 minutes of mouse movements. But if Ascott’s internet was first intimated by his encounters with the technologies of state surveillance, today it’s the corporation that provides the most reliable window to our technological future.

Eight years before DARPA’s Active Authentication, Google filed a patent for a “system and method for modulating search relevancy using pointer activity monitoring.” The system records the pointer movements of Google users to improve the relevancy of their search results. Competitors like Facebook, Amazon, and Apple quickly followed with gesture capturing technologies of their own. Two decades later, this gestural gold rush has precipitated a host of wrist-mining technologies in the form of smart watches, gyroscopic VR controllers, and gesture-navigated screens. Less conspicuously, it resulted in the revision of boilerplate terms of service agreements that now include our pointer movements and typing rhythms as corporate property. By the time DARPA began researching cognitive fingerprinting in 2011, Microsoft had already developed reliable algorithms for predicting users’ eye positions on the screen through their gestures alone. Soon afterward, Facebook incorporated similar predictive frameworks into its ad pricing algorithms. Billion-dollar economies, now moored through the relentless tracking of loose limbs to predict our cognition. In other words, you’re a human software extension too.

This new corporate phrenology not only relies on the pervasive extraction of data from our bodies but shapes environments around us that are premised on a different conception of life itself. A postdigital ontology intimated in Ascott’s own bodily reprogramming half a century ago. In scripting himself as an information network, Ascott undermined modernist painterly traditions that conceive of the gesture as the outward evidence of a subject’s authentic interior. To read a gesture usually implies the application of specific techniques of analysis intended to reveal the hidden interior of a subject. Implicit in this conventional understanding of the gesture is a biopolitics of surveillance designed to expose private interiors by treating gestures as windows into souls. But the “beams” of information scripted in Ascott’s field games, and later monetized by big tech’s analytics oracles, suggest a different technopolitics of the gesture that Byung-Chul Han calls the psychopolitical.

While often misconstrued as surveillance, biometric mining relies on an alternative formulation of life in which there’s simply nothing left to surveil. Rather than subjects, with hidden interiors that must be uncovered and controlled, these technologies operate on users. The attributes of a user exist only insofar as they are addressable by information processing systems. When your pointer movements are harvested to optimize search results or to price online advertisements, these gestures aren’t windows into the veiled recesses of an inner self, but technologies designed to turn your insides out. They render the murky fluctuations of your attention, feeling, and mood addressable by exteriorizing them in your mouse movements. Through biometric datamining, Han writes, “the negativity of otherness or foreignness is de-interiorized and transformed into the positivity of communicable and consumable difference.” If the soul presented a blockage for older regimes of power because it was hidden, today the soul is troublesome simply because it doesn’t generate any content. On the internet of loose limbs, all things must be accounted for through the positive production of information – information generated when a user moves. And with just the right algorithm, the soul can be remade to move through the wrist.

Today, our captured gestures make the future a little more tangible, but only for those with the resources to process them. In 2010, Amazon began developing a gesture-based user-authentication system to distinguish human from nonhuman users. Initially intended to filter the automated price-scanning bots of competitors like Walmart, a by-product of this system was the enormous trove of pointer data detailing the patterns through which our bodies interact with Amazon’s platform. In isolation, these data points say little about our private desires, but in aggregate, their diversity builds probability models that anticipate our future interactions with the platform.

Two years after Amazon began capturing the gestures of their customers, they introduced the Buy It Now button. Since its introduction, the button has been relocated 15 times, moving between 10 and 100 pixels with each makeover of Amazon’s user interface. These subtle relocations, defined in part by our aggregate gesturing, optimize the button’s location to narrow the window between impulsive gestures and second guesses. Living as a software extension not only entails the pervasive extraction of information from our bodies, it also means that this information builds predictive products that parcel our futures into probability distributions that can be bought and sold. Our movements move the button so that the button can eventually move us; a Cybernetic Art Matrix with two-day delivery.

Cooperative Intuition

As the fourth month of the two-week quarantine wore on, I felt like doing something more constructive with my own predictive products. Eventually, I built a machine to drip my growing archive of lines out as lumpy little pie charts on silicone sheets. Each line slowly formed out of a few hundred droplets of paint; each droplet comprised of two to eight colors – indexing the specific number of workers sampled to simulate the line itself. Each line congealed out of fluid acrylic and the probable movements of human software extensions. Once dried, I’d peel the wobbly lines from the silicone sheets and assemble them into objects that were heavy like sculptures but hung like paintings. I called them plans, as in low-tech analogs for planning a digital network to come.

To be honest, it all became an obsession that’s difficult for me to explain in retrospect. For months I worked to perfect the viscosity of bespoke paint formulations; I designed and redesigned systems of pumps and funnels to compress the entire spectrum into a single droplet; and I became intimately familiar with the differing pigment densities of dioxazine purple, cobalt blue, and cadmium yellow (light hue, never medium). All while rewriting RandomMap-finalfinalfinal.js every few weeks to better optimize my database of captured gestures. Each new simulation extracted unexpected qualities from the biometric database, suggesting new compositional possibilities for plans to come. Over and over, I’d scrap what I had, rebuild the machine, reformulate the paint, and redesign the assembly process of the plans accordingly. Friends would ask when I’d have something to show for it all, and I’d usually say, “Pretty soon.”

At some point, it occurred to me that between the combinatory possibility of 100 workers’ wrists, the entropic puddles of dripping fluids, and my own instinctive culling of thousands of simulated lines, the whole enterprise was being propelled by a kind of cooperative intuition. A creative agency unevenly distributed through me and my instruments, the workers and their data, and the unstable behavior of paint dripping from a hacked-together machine. Roy Ascott might call it a Cybernetic Art Matrix – one in which the predictive products that now monopolize our futures are made to behave badly. Rather than parceling what’s to come into controllable probabilities, RandomMap.js distributed authorship unpredictably across time and distance. Every 30 minutes, spitting out 100 lines authored somewhere between a JavaScript code I wrote last spring, the bodily movements of faraway workers mined the winter before that, and 100 ad hoc chimeras – compound bodies gesturing gestures to come.

Along with this realization came the sense that my own obsessive tinkering suddenly comprised decisions that were no longer mine alone to make. In other words, that a body of work that began amid the extreme isolation of quarantine now belonged to a distributed network of people, machines, and matter. An art matrix that might be organized around an alternative economy of authorship; one in which my first-person singular was replaced with our networked togetherness. So, in conversation with the workers that first informed the gestural database, we drafted a cooperative charter for managing our little parcel of the future more equitably. It goes like this:

1. Anybody can remove their gestures from the database at any time.

2. Before each simulation, anybody can modify their gestural profile.

3. After each simulation, every randomly sampled person is paid royalties at a set rate.

4. Each line included in a plan is collectively owned by the people sampled to produce it.

4a. Each individual’s ownership share of each line is proportional to the statistical weight of their gestures sampled to produce it.

5. Each plan is collectively owned by the shareholders of each line used in the plan.

5a. Every line in a plan is equally valuable.

6. I retain the right to decide when a plan is produced, to select the most useful lines, to assemble them into desirable compositions, and to choose the color palettes.

7. The asking price of each plan is determined democratically by its shareholders.

8. All plans must be sold.

9. All of the proceeds from each sale are distributed to the plan’s shareholders proportionally.

9a. Any member has the right to extract cultural capital from the work in the form of artist talks or texts like this.

9a-1. Any associated honoraria are distributed equally to the entire group.

10. Any structural changes, like ending the project, are determined democratically by the entire group.

We call it a “platform cooperative,” one in which every individual owns the information their bodies produce and the group collectively owns the future of our shared gesturing. While each person can withhold their labor, we’re organized less around the value of any individual’s data than the figures our dataset produces in aggregate. Seventy-two of the original 100 workers signed-on, I added my own wrist to make it 73. In the months since, we’ve collectively redesigned what DARPA once called our cognitive fingerprints, adding new gestural parameters to the collection, which inform the simulation of lines with more diverse graphic qualities, and transforming the database itself into a space for the collective authorship of our compound identities – 73 individuals seeding a spreadsheet with unexpected forms of diversity by beaming our loose limbs in novel ways. In turn, each RandomMap.js simulation now results in lines that are always a little more unexpected than the last. I save more, delete less, and eventually intuited the criteria for their collection in a set of graphic standards shared in a Google Doc with the rest of the group. The fourth plan sold for twice the price of the third, the fifth for half again as much as the fourth.

Together Forever

In The Ministry for the Future, Kim Stanley Robinson makes the observation that democracies represent the future poorly. Because votes aren’t allocated to those who don’t yet exist, the ones who will live with our decisions tomorrow are the ones who are denied a political voice today. While his observation concerns our inability to confront climate catastrophe through our present political economies, today’s internet of loose limbs exploits this same failure of our political imagination. When data is mined from the movement of your wrist, what’s valuable isn’t the data as such, but its predictive potential en masse. Through sheer scale, these processes turn the banal details of our bodies into predictive products that appropriate our futures. From Uber’s “god view,” divining your divorce through your ride history, to the CIA’s prediction of your citizenship in real time through your browser activity, our bodies now seed datasets with the protean diversity required to calculate our most intimate probabilities at unimaginable scales. The violence these processes entail isn’t so much a violation of our privacy as the enclosure of our futures.

As information-capturing economies transform life into a substrate for extending software, we’ve failed to advocate for the future as a public commons. Recent legal activism like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) prioritizes data privacy as private property, while failing to give the public agency over the prediction products our bodies now inform. As Katrina Forrester observes, “Policies to protect privacy appeal to a language of transparency, individual consent, and rights. But they rarely try to disperse the ownership of our data – by breaking the power monopolies that collect it, or by placing its use under democratic control through public oversight.” But whether it’s Ascott’s coin flipping, the AIA’s standard contract documents, or a Google Doc charter for a wobbling platform co-op, making anything together requires a political economy for managing the uncertainties of what’s to come. Rather than the exploitative norms of contemporary architectural practice, or the psychopolitical violence of humans as software extensions, we should see our authorship as opportunities to create new political economies, better ways of living together, and more equitable systems for distributing our futures. While all of this might pale in comparison to the vast scale of technologies now arrayed around our biometric extraction, developing forms of togetherness that are other than those prescribed by social networks designed to relentlessly individuate us makes a better future a little more tangible.

After finishing the sixth plan in the series I felt like moving on – doing a different kind of work. Friends asked where all of this was going, and to be honest, watching rainbow droplets dripping in an unconditioned warehouse wears you down eventually. While I wrote this, I proposed ending the series in a Google poll sent to the rest of the group – something like going out on a high note. The group rejected my proposal by a 58 percent margin. The seventh plan should be ready pretty soon.

|

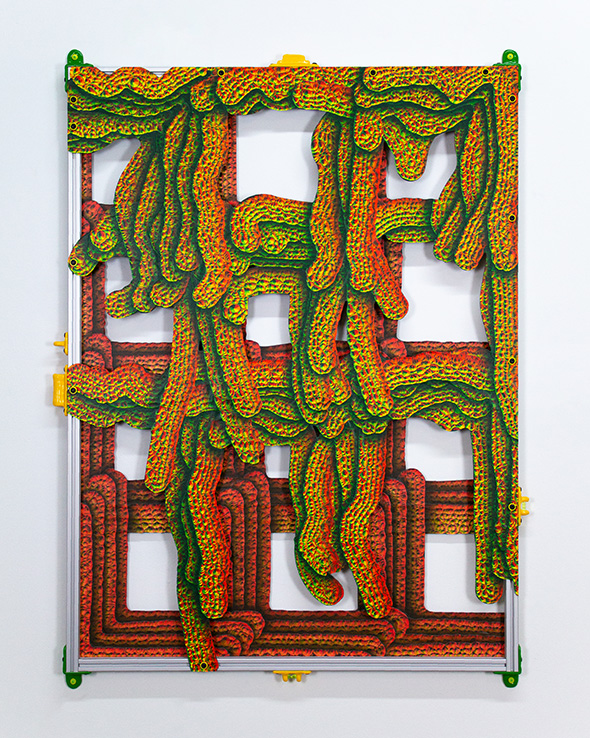

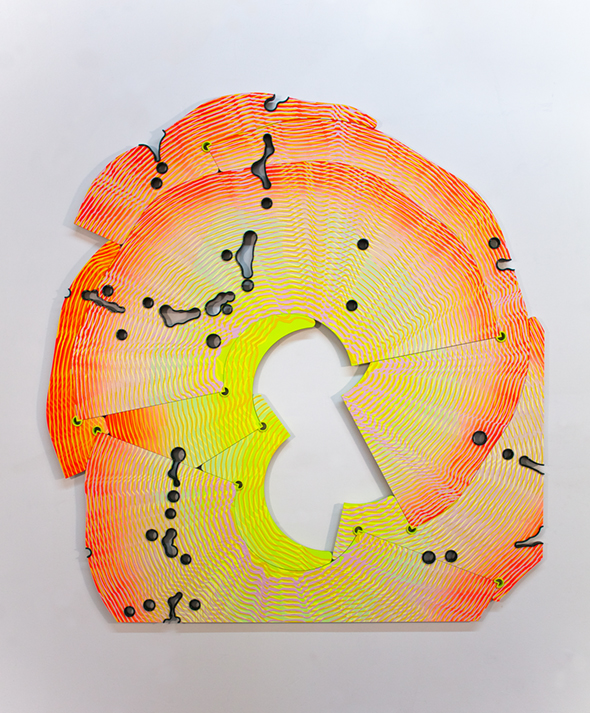

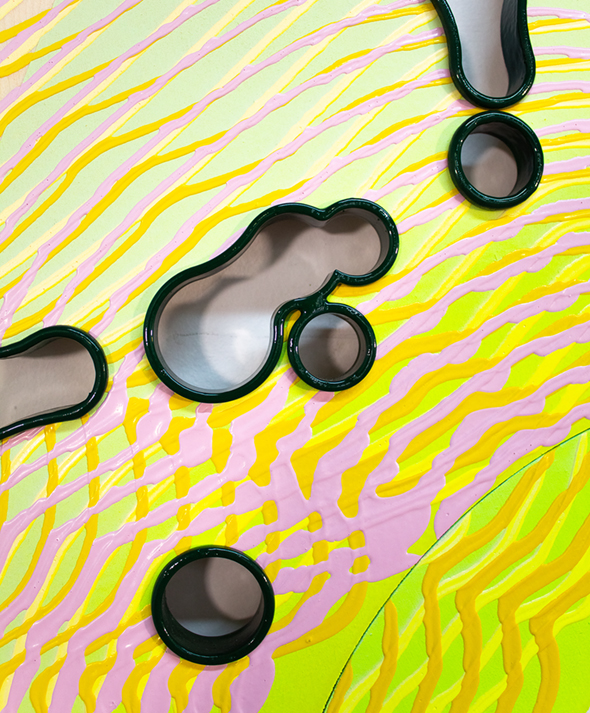

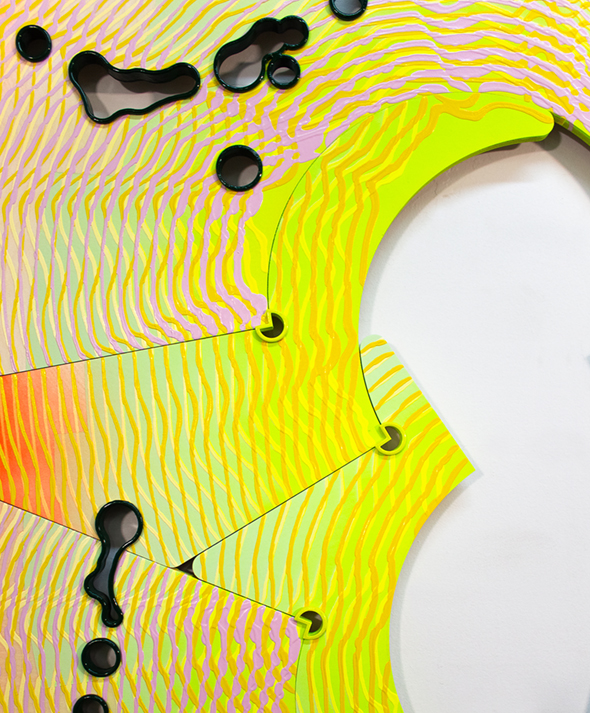

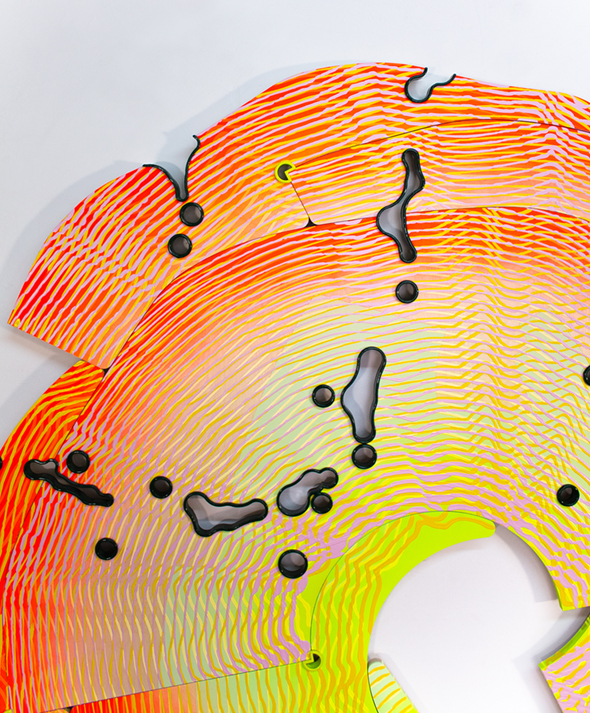

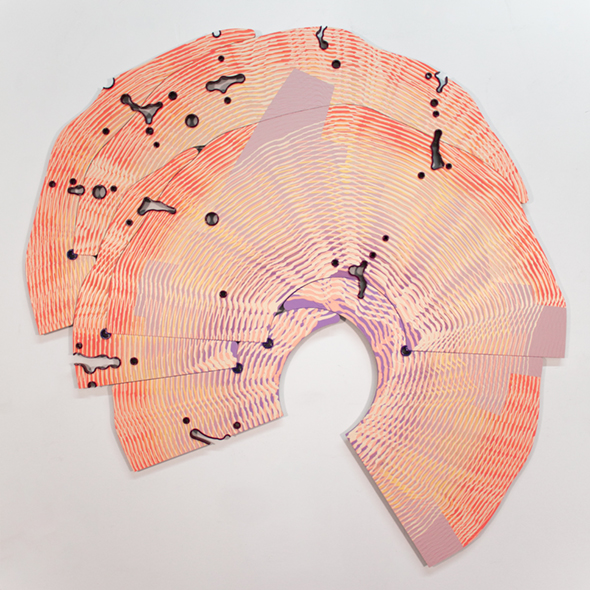

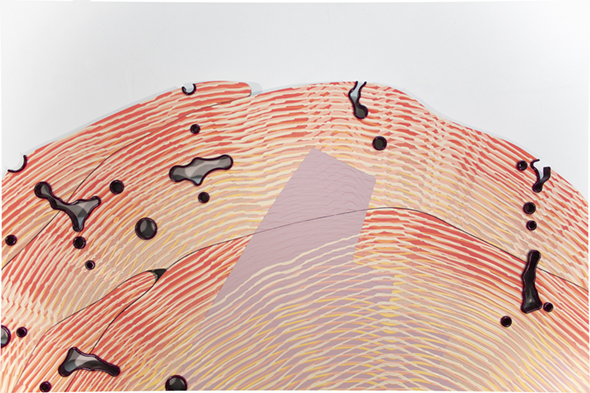

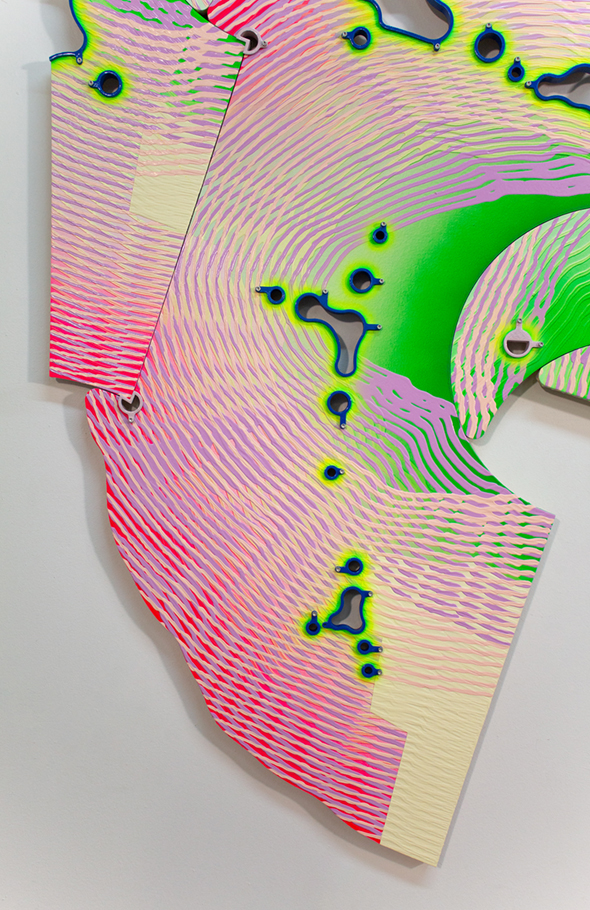

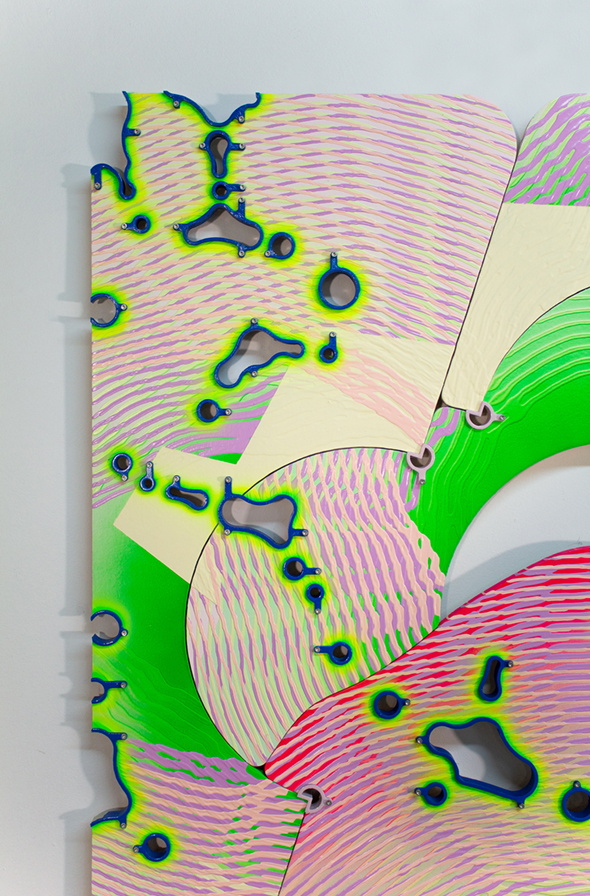

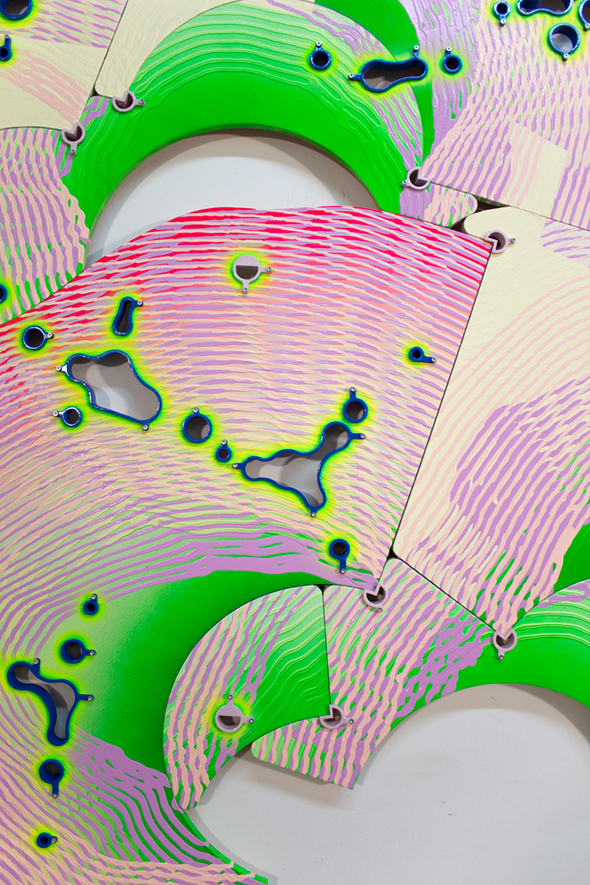

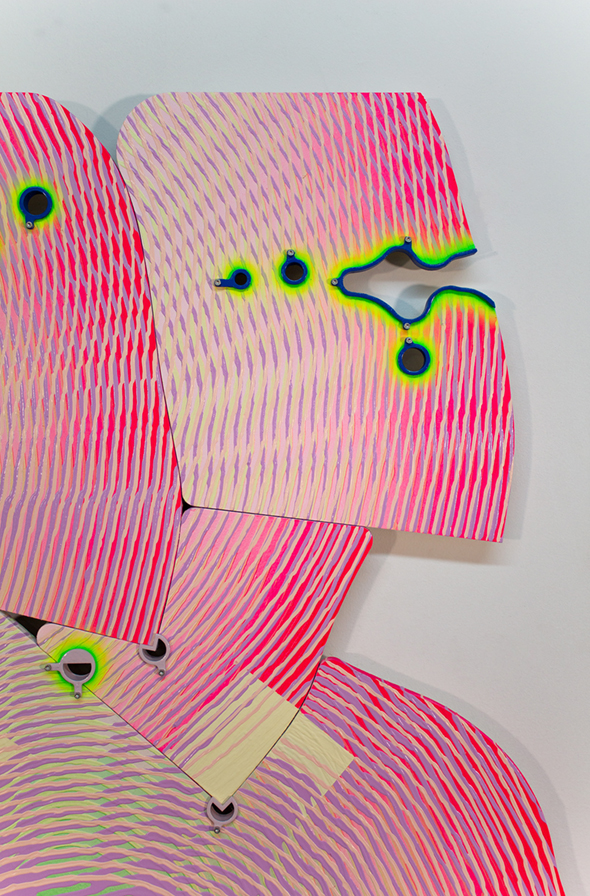

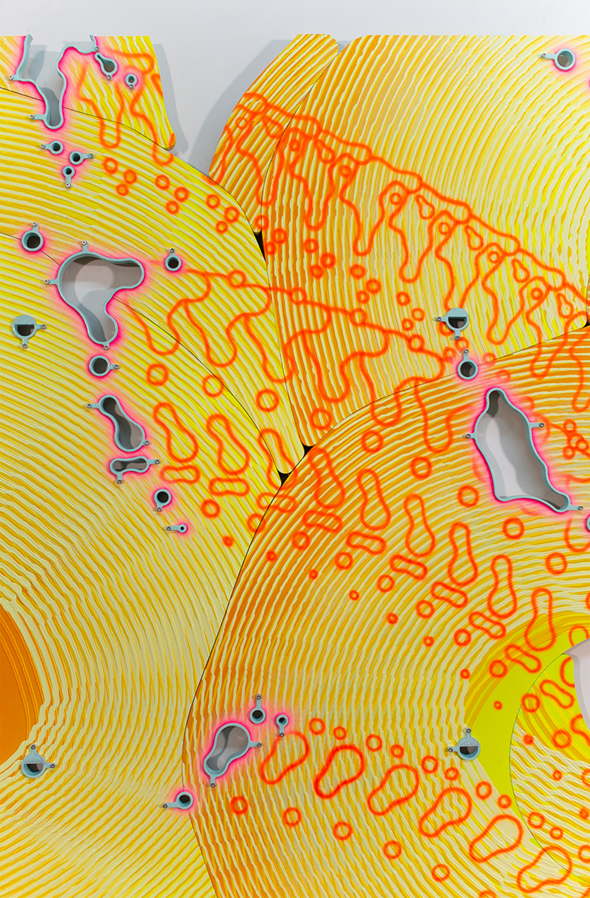

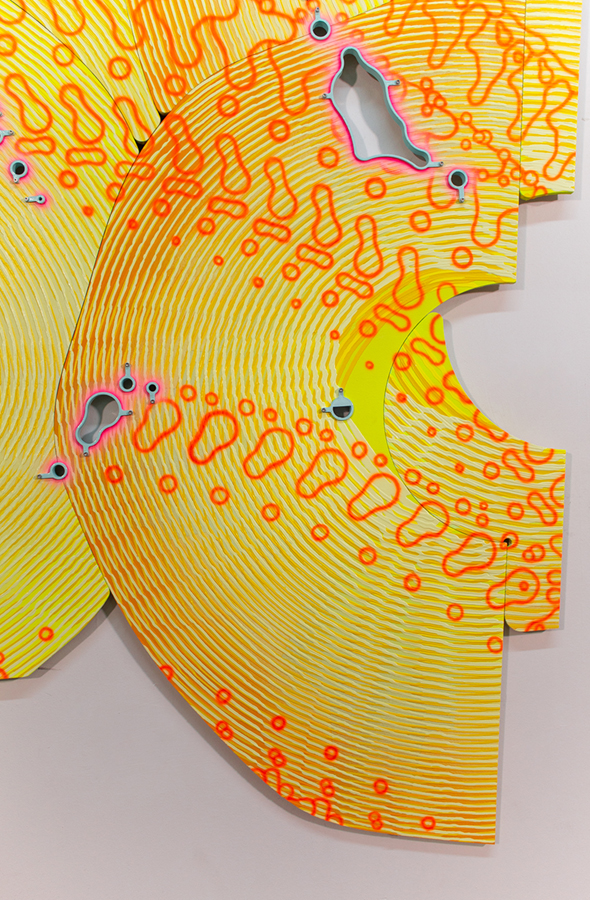

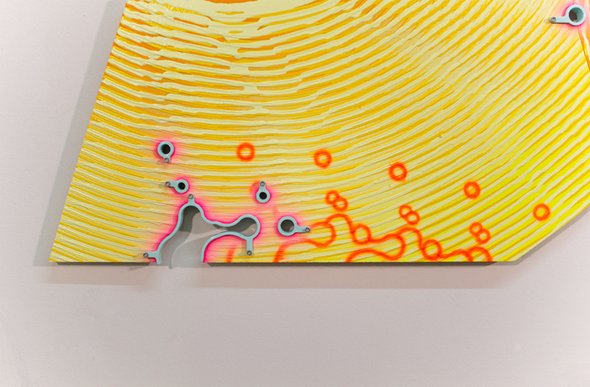

♺ CHARTER PAINTINGS ♺

[PAINTING] For fun

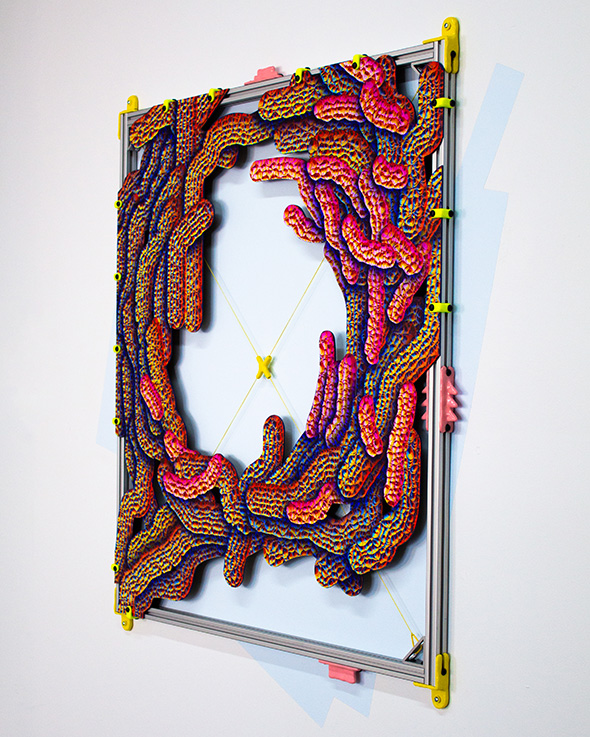

![]()

Charter Painting 04, 2022

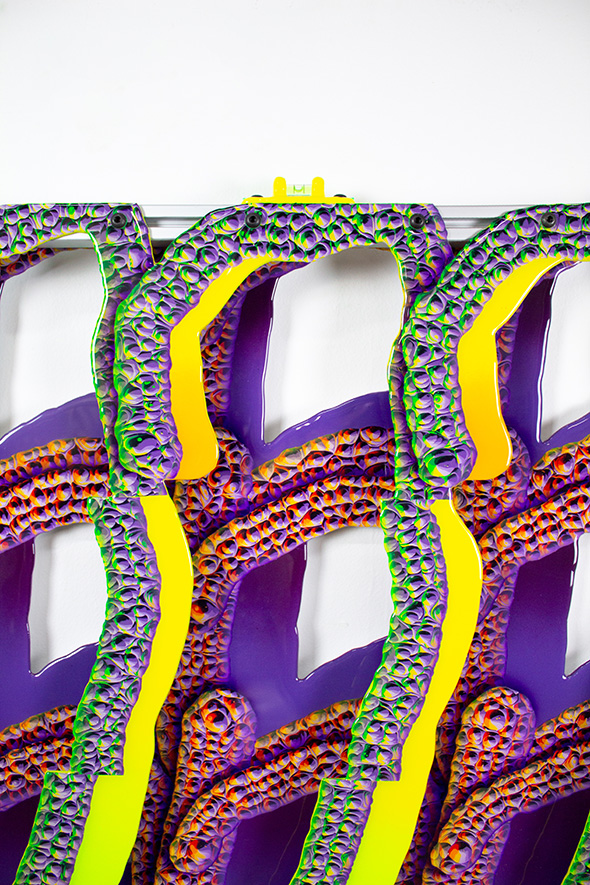

Paintings produced with a machine, software, groups of people online and a charter that explored ways to distribute money for creative work more equitably. For more information, see: Together Forever, LOG 54, 2022.

![]()

Charter Painting 04 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 04 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 01, 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 01 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 01 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 02, 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 02 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 03, 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 03 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 03 (detail), 2022

![]()

Charter Painting 03 (detail), 2022

|

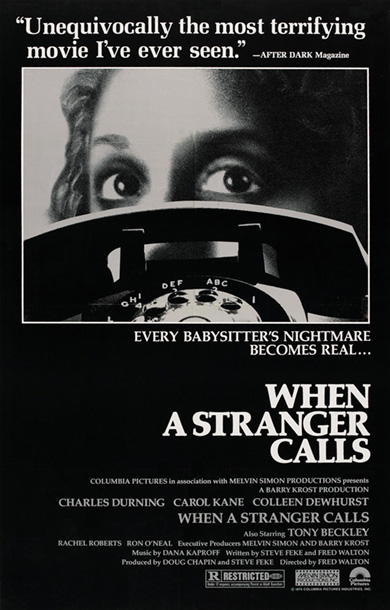

🝪 WHEN A STRANGER CALLS 🝪

[TEXT] 2020_Who really knows...

![]()

A 5G tower burns in Coolville, Ohio, 2020

In 1960, a young biophysicist named Allen Frey was working in General Electric’s Advanced Electronic Center at Cornell University when he was visited by a stranger. This stranger, a radar technician from a remote corner of the laboratory, reported to Frey a peculiar ability. Namely, to hear the radar signals he was supposed to be monitoring telemetrically. Skeptical, Frey visited the stranger’s workstation and to his surprise, discovered that he too could hear the barely audible clicks and buzzes reported by the technician as the radar oscillated through its frequencies. The observation would soon become known as the Frey Effect: that microwave pulses at precise wavelengths precisely fry the brain. As the brain cooks it expands and contracts, placing pressure on the cochlea. Scientists call it a thermo-elastic expansion of the auditory apparatus, allowing subjects to hear something like sounds that have bypassed a vibrating eardrum altogether. Higher cooking temperatures soon led to higher auditory resolution. By 1975, deep fried researchers at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research were able to decipher nine out of ten words through unevenly cooling brains in a method the public would eventually call Voice-to-Skull communication or V2K.

Since its Cold War discovery, Voice-to-Skull communication has become something like conspiracy Tupperware. A free-floating technology, equal parts plausible and perfectly terrifying enough to package a host of contradictory conspiracy narratives, ranging from Soviet psychotronic nautical warfare to Freemason mind control endeavors. In lieu of an accurate history, the highlights are as follows:

1) From 1953-1976 a microwave transmission known as the ‘Moscow Signal’ was directed at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. In 1965, DARPA launched Program Plan 562 (Project Pandora) to discover whether the Soviets were using the Moscow Signal to influence the behaviors of embassy workers.

2) In 1987 the Army Research Institute documented a sharp rise of references to psychotropic weaponry in the popular press. Most notably, Soviet V2K technology was commonly cited as a possible cause for the unexplained sinking of U.S. submarines the USS Thresher and Scorpion in 1963 and 1968 respectively.

3) In 2003, WaveBand Corp. secured a contract with the U.S. Navy to develop a Voice-to-Skull weapon called MEDUSA (Mob Excess Deterrent Using Silent Audio). The outcome of this research remains classified.

4) In a meeting between Russian Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov and President Vladimir Putin in 2012, Serdyukov reported that Putin claimed a significant portion of his 770b USD arms budget would be devoted toward the procurement of emerging ‘psychotronic’ weapons.

5) Since 2017, over two-dozen workers in U.S. embassies in China and Cuba have reported feeling dizzy, vomiting, and hearing inexplicable sounds. A medical team at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Brain Injury and Repair has theorized that V2K microwave weapons are probably the cause.

6) In 2018, Former NSA spy Mark Beck claimed his Parkinson’s disease was caused by a psychotropic attack from an unnamed foreign power.

7) On January 29th, 2019, popular right-wing figure QAnon speculated on the potential relationship between Voice-to-Skull technology and the activities of a U.S. Deep State in drop #6329, claiming, “>>4957311 (PB) V2K about to be exposed?”

Like other pseudo-tech such as chemtrails or UFOs, Voice-to-Skull is politically promiscuous. But its popularity isn’t only the product its technical plausibility, V2K’s allure as an anchor for a half-century of conspiracy narratives from across the political spectrum stems from its ability to conjure a specific type of terror that underpins the conspiratorial mode itself.

Inside Terrors

The 1976 slasher film When a Stranger Calls earned its cult status with its opening depiction of a popular urban legend: The children are asleep upstairs when their babysitter Jill receives a phone call asking her if she’s checked on the kids. Jill dismisses the call as a practical joke. But as the calls become more frequent and threatening, Jill calls the police, who ask her to keep the threatening caller on the line long enough for them to trace the call’s origin. After receiving one final call from the stranger, a breathless officer calls back to inform Jill that the stranger is calling from inside the house. Jill runs for the door, as a light comes on behind her, and the stalker’s shadow appears. The terror of this now-infamous opening sequence is the same terror that has made V2K such a compelling vehicle for conspiracy narrative since Frey’s discovery sixty years ago. That is: the abrupt horror of insides turned out; of suddenly doubting the clean partitioning of one’s mind from the world it occupies. With V2K, the skull’s interior is annexed within an unimaginably vast telecommunications network, and the privacy of your own thoughts are no longer yours alone.

![]()

When a Stranger Calls, 1976

Five days prior to the QAnon reference to V2K, popular Christian YouTuber Dana Ashlie released an interview with an unnamed (and unseen) former DHS employee who claimed the United States’ 5G roll-out was a front for a clandestine nationwide expansion of existing V2K infrastructure. The video was seen over a million times, and the story soon mushroomed on a host of adjacent right-wing internet conspiracy communities. Importantly, given its micro-wavelength, 5G signals have an effective range of around 1000 feet, compared to 4G’s effective range of around 10 miles. Proponents of Ashlie’s theory noted that the increased density of signal towers associated with the 5G roll-out seemed to correspond with Allan Frey’s observations that the Frey Effect is most distinct under 1000 feet. According to Ashlie, the transcontinental conspiracy involved unnamed deep-state agents, piggy-backing nefarious sub-2GHZ frequencies atop the innocuous 24GHZ frequencies of standard 5G signals for the purposes of global mind-control.

While a general rule of the internet might be something like: somewhere you can find someone who believes anything. In the months following Ashlie’s interview, the connection between 5G and V2K proved to be unusually popular. By mid-2019 it had migrated from niche platforms like 4chan to mainstream social media sites like Twitter. By early 2020, Best Buy was sold out of handheld spectrum analyzers and amateur investigators were mapping the relationship between detectable sub-2GHZ frequencies and the expanding network of 5G towers across American cities. While telecommunications experts were quick to point out the inefficiencies of such a massive clandestine undertaking, the V2K/5G connection endures precisely because any doubt in the conspiracy narrative can always be understood as an effect of the technology itself. After all, if global mind control is possible, who’s to say our skepticism isn’t just a deep-state broadcast? But perhaps more fruitful than whether our thoughts are really ours or not, might be why such a seemingly arbitrary alignment between niche conspiracy technologies and common cellular infrastructure is so persuasive right now. In other words: what compels us to feel this particular type of terror in this particular moment?

Theorist Timothy Morton has identified the terror of turning insides out as a crucial trope of noir storytelling. According to Morton, the noir private investigator typically begins their case as an observer, external to the mystery at hand, only to eventually discover that they are complicit in the mystery they thought they were merely observing. The stalker is calling from inside the house, the deep-state from inside your brain. The noir terror of V2K relies on the sudden realization that there is no metaposition, that even our own cognition has been conscripted into a vast technological network. Morton diagnoses the ubiquity of this noir mindset today as a symptom of what he calls the ecological thought. A broadly felt destabilization of modern subject/object binaries that have prioritized intellectual remove amidst a networked climatological unraveling we can no longer remove ourselves from. There are no metapositions at the end of the world. For Morton, this means we increasingly find ourselves living as noir protagonists, continually confronting the terror of being caught in the intricate entanglements through which life, technology and capitalism are intertwined. And the dense network of 5G towers now being installed in cities across the world promises nothing if not the intensification of those networks we find ourselves caught within.

The Smart City

The funny thing about the intensity of the 5G roll-out now surrounding us is that nobody can recall feeling like 4G wasn’t fast enough. Rather than an accommodation to consumer demand, the rapid development of 5G networks across much of the world is largely due to 5G’s critical role in the expansion of the smart city. This smart city to come will necessarily rely on an extensive array of sensors and data processing operations intended to improve the efficiency, and increase the profitability of urban environments. Although smart devices such as smart televisions, refrigerators or phones, already play important roles in our daily lives, these early offerings already consume a significant portion of the available 4G bandwidth. Telecommunications corporations like Verizon argue that the full realization of the smart city, including self-driving cars and automated delivery technologies, will require a radical expansion of the available bandwidth that is only achievable with a 5G network.

But while the smart city is usually represented through the dull shine of seemingly innocuous innovations like self-driving cars and automated delivery bots, in practice, it is a far more intimate affair. Theorist Jathan Sadowski likens the fabrication of the smart city to terraforming – wherein the objects that comprise the backgrounds of our daily lives are transformed into instruments for collecting and broadcasting information. Like the terraforming of a distant planet in order to make it habitable for human life, the contemporary terraforming of the city centers upon reengineering our homes in order to make them compatibility with an emerging regime of surveillance capitalism that profits off of the circulation of user data. So while it’s represented through appealing conveniences like self-driving cars and automated delivery drones, the smart city is altogether more banal – like an online door lock that knows you’re having an affair and upsells you faster-acting sexual enhancement pills in discrete packaging. In the smart city, 5G is the guarantee that the strangers calling from inside your home will always have a signal.

Seen in these terms, clandestine Voice-to-Skull networks and totalitarian thought control suddenly seems a little less outlandish. While the transformation of our most intimate domestic spaces into digital surveillance networks might not be the voice of the deep-state frying our inner ears, it’s the next best thing. Like the noir terror implicit in Morton’s ecological thought, the smart city doesn’t just watch us, it is us. It’s our habits that train its machine learning models, it’s our most intimate information that is bought and sold by data brokers, and it’s our simulated unconscious that directs its predictive marketing algorithms. But if our lives are the raw material for producing the smart city, and if that process of production depends on the high-speed connectivity of 5G networks, then perhaps turning out insides out isn’t entirely inevitable.

However delusional it might be, the broad paranoia surrounding the rapid expansion of 5G technology suggests an emerging public concern over the ownership of our networked selves. While V2K activists rightly argue that the ability to direct our own thoughts should be considered a universal freedom, the argument should really be for a new technopolitics altogether, one in which the ability to direct our data would be regarded as both a human right, and a vehicle for dismantling digital capitalism. The Voice-to-Skull conspiracy community is nearly unanimous in its demand to cleave the self from the networks of technology it is caught within, and problematically, most of the voices advocating against the smart city’s encroachment into our lives have mirrored this same argument. In her recent essay Known Unknowns, Karina Forrester argued, “Policies to protect privacy appeal to a language of transparency, individual consent and rights. But they rarely try to disperse the ownership of our data – by breaking the power of monopolies that collect it, or by placing it under the democratic control through public oversite.” Instead of merely privacy, instead simply evicting the stranger from our homes or the deep-state from our heads, this new technopolitics should regard the production of user information as a form of alienated labor. It should understand the product of that labor as an invaluable shared resource. And it would demand democratic control over how that information is used, by whom, and to what ends.

And this is precisely why 5G is such a crucial element within this narrative. While our democracies have largely failed to ensure the equitable management of our information, this is largely due to the simple fact that our political structures are materialist in nature. And it’s within the realms of material management, from the conservation efforts of the National Park Service, to the public protections afforded by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that our systems of governance have proved most just. If the new empires of smart data depend on a vast 5G network enabled by public political processes, then these processes must be made to contest not only where such towers do or don’t go, but who will benefit from the information circulating through them. Redefining the legal status of our information against the seeming inevitability of the smart city will undoubtedly be an uphill battle. And until we win our rights to the nascent smart empire circulating through 5G towers, we’ll be burn them down.

|

෴ GESTURING ELSEWHERE ෴

[DRAWING] 2020_cOmInG SoOn

|